As you’ll read in Part Two of Julie Woodyer’s story, she fought to stop the Alberta government from culling wild horses and demonstrated that they are not the cause of damage to rangeland.

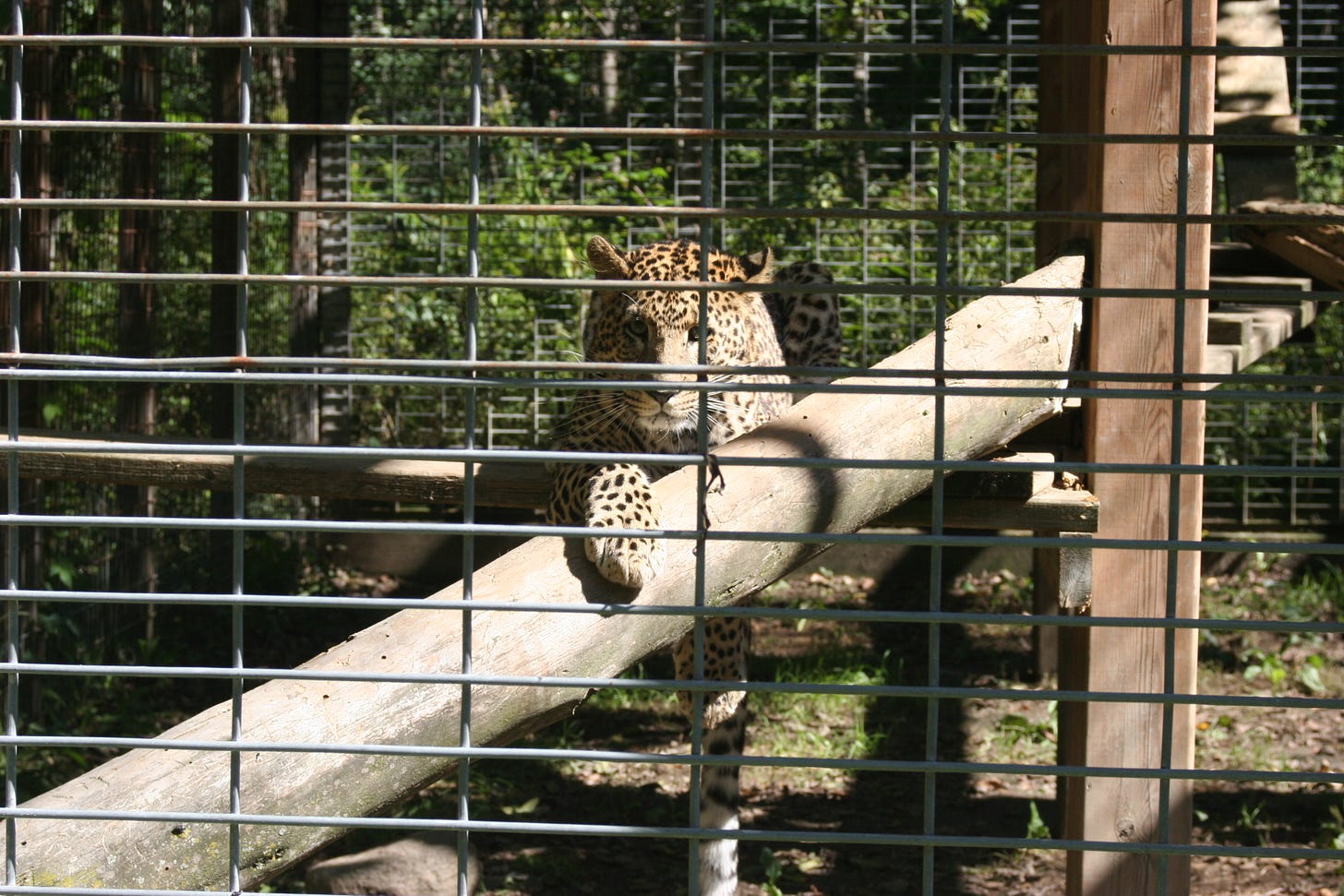

In October 2022, Julie and I toured the Elmvale Jungle Zoo. Julie was there to research and record the state of the animals for a report she was working on, and I was there to see her in action. It was difficult to witness these beautiful creatures in distress, and the first time I visited a zoo—which I haven’t done frequently—since becoming vegan. Many big cats displayed stereotypical behaviour, manifesting as chronic pacing in their small enclosures. This type of abnormal behaviour has only been witnessed in captive animals and it’s directly due to the unnatural environments and conditions forced upon these animals. Julie took the video below during this visit.

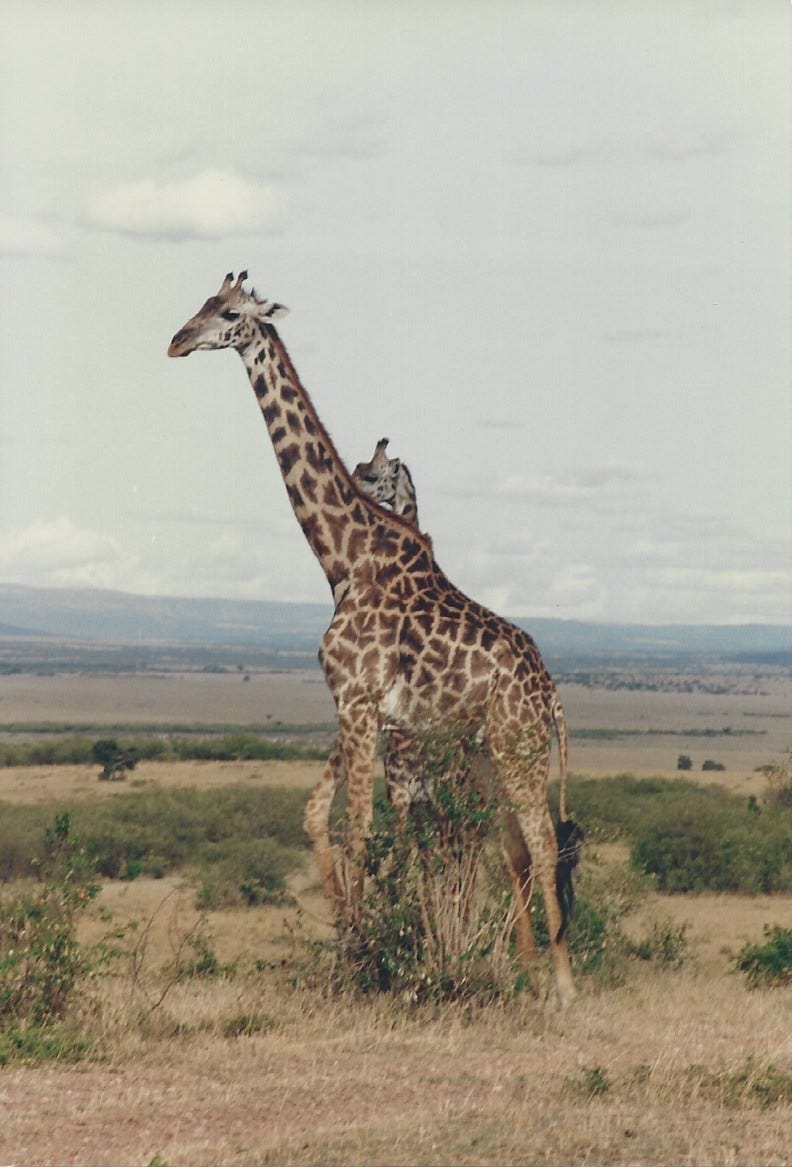

In 1991, I travelled to Kenya and did a one-week safari in the Masai Mara National Reserve. To this day, my trip to Kenya remains my most treasured adventure. I saw wild animals in their natural habitat, behaving in ways that are typical for each species. The only “shooting” that was taking place on this safari was with our cameras, and we were the interlopers on their territory with strict guidelines to minimize our impact, albeit we did get a herd of giraffes on the run when flying above them in a noisy hot air balloon.

During one of our daily expeditions in the Reserve, I witnessed a mama cheetah training her young ones how to hunt. They captured a young gazelle before my eyes. They didn’t kill their catch right away, they were holding it down with their paws, although we all knew its fate.

It’s an extraordinary experience to witness wild animals in their natural habitat; who among us hasn’t been in awe when we see a whale breaching from the depths of the ocean?

What I saw at the Elmvale Zoo was remarkable in all the wrong ways. Lions, tigers, one lonely leopard, a cougar and other wild cats confined to small enclosures prevented from running and hunting is anything but natural. Suppressing their instincts is detrimental to their well-being. Zoos are often promoted as educational for children, but we have to ask ourselves what sort of education they are getting.

Much of the work at Zoocheck is political and about changing laws. “In our experience, it's very difficult to change public opinion sufficient to truly protect animals, and that's because we don't have the ear of the vast majority of people. We have the ear of a sympathetic minority.”

Julie says that their progress is often temporary, citing the case of the spring bear hunt returning to Ontario when there was a change in government. “It's a hard go working for animal protection. But I can say I've seen a lot of change in my career and particularly in the last ten years or so, a lot of attitude changes. But the attitude changes have somewhat followed the laws, and the laws changed because people were at risk, not because animals were at risk.”

She goes on to give examples of trainers being injured while attempting to train a wild animal to do something completely unnatural, like all the whales and dolphins held in captivity at Marineland, or people who thought it was perfectly acceptable to have a pet monkey—that is until their child was hurt by the monkey simply behaving instinctually.

Another area of work Zoocheck is involved with is mobile live animal programs, also known as MAPs. These programs transport animals from event to event, for example, CNE’s children’s events, to put them on display, essentially a mobile zoo. And just like zoos, the animals exist—because you can’t call it living—in unnatural environments and are in poor condition. Unlike roadside zoos, MAP living facilities are not open to the public therefore their conditions can’t be monitored by people like Julie, and she tells me that the way they are transported and displayed “equates to essentially a Tupperware container with holes in it. In particular, reptiles are housed in aquariums that are devoid of any real natural environment for the animals. I suspect that a lot of their permanent facilities are similar, just a barren pool for a turtle, for instance, with a small hollowed area. Meanwhile, turtles live these highly complex lives in and out of water, and some turtles will stamp their feet on the ground to get worms to come out.”

The death of Kiska the lonely orca at Marineland is a sad reminder of the work that remains to protect all wildlife. Captured in 1979 at approximately three years old, Kiska had been imprisoned in a small tank for most of her life. For more than a decade before her death on March 9th, she was alone, having outlived all her calves.

There are several beluga whales and bottlenose dolphins that remain in captivity at Marineland, the park that is famous for all the wrong reasons.

While other non-profits do similar work, Zoocheck is whom grassroots organizations worldwide reach out to for help. For example, a couple of years ago, Zoocheck was approached about the issue of many lone elephants in zoos across Japan. They hired an elephant biologist to go to Japan and assess the living conditions for these elephants who were living without another of their species. The idea was to perhaps “consolidate them as a herd, or to at least improve their circumstance for the remainder of their lives,” says Julie.

From that assessment, a report was written and given to the Japanese activists who could in turn talk to decision-makers about how to help these elephants.

“We get lots of requests, and I think we're one of the few groups that is always assisting somebody because we see it as having greater success if we prop up a smaller organization in their home country, give them the tools they need to do the job. To be effective, you have to partner with local organizations. In truth, they're best positioned to understand the political and cultural environment.” This also applies within Canada.

A current Zoocheck campaign in the Wildlife Management sector is the cormorant hunt in Ontario. The 10-minute video called Shoreline Socialites released by Zoocheck in October of 2021 explains what they are up against in this fight to protect double-crested cormorants.

Another long-term project is the wild horses in Alberta, which until a few years ago had been regularly culled, mostly from rancher complaints. In Alberta, ranchers pay a small fee that allows them to let their cattle graze in the foothills. “Essentially, the government supplements the cost of feed for the beef industry. That creates competition for any other animal in the ecosystem that eats grass,” explains Julie.

But beef cattle is the species that is damaging the rangeland, not the wild horses. “What they fail to acknowledge is the biology of the animals. For instance, the way cows eat is they grab the grass and they tear it out by the roots, so it takes much longer for grass to regrow when the roots are not intact. Horses chew off grass, essentially like cutting your grass, and it doesn't destroy the ecosystem, yet the horses are attributed the same amount of damage per animal as a cow. We've had a lot of success in the campaign. They quit culling about five years ago, right after we released a report by a biologist who deals with wild horse issues, and he was dispelling all the myths and showing how the government programs were not scientifically based.” But there’s always the danger of the cull resuming, which is why Zoocheck keeps on top of this issue.

“We do our own wild horse counts. The government had been doing it themselves and we're not confident in what they've been doing, so we're doing our own. That's very expensive because it has to be done by helicopter to be able to see the animals, but it's an important process to keep the government honest.”

Julie was interviewed about this issue in a segment of W5 from 2015. You can view it here:

Our feathered friends are often ignored in the animal rights fight but suffer greatly. Parrots kept as pets in North America die prematurely, often within their first year.

Julie shares how birds of prey are trained to scare gulls away from public spaces, such as outdoor concert venues, and then to come back ‘home’ for food. And some of these birds are “tethered on the ground almost all day long or in small, decrepit cages.”

Despite all the years of hard work that Zoocheck and Julie have done and continue to do, she’s not optimistic that we’ll “be able to turn this around” in terms of the state of the planet. But she will continue to do her part for animals who suffer at the hands of humans.

“If I can at least reduce the suffering of as many individuals as I can help, of whatever species, then I sleep at night knowing I did something today. To help someone else not suffer—that someone else might be a bear, a chicken, a human. Or it could be a river or a lake, too. If I can just do a little something that reduces that suffering, then I sleep at night.”

At the same time, Julie believes animal activists and animal protection agencies must play a bigger role and that the wheels of change are not turning quickly enough. She fears that the majority of humanity will wake up to the truth of what we are doing only when they are forced to.

“I think our biology and our big brain are working against us and the rest of the world. At some point, there will be a tipping point. I don't know where we'll be then or how many species will be extinct and how many individual animals will have suffered and died, but it'll be billions—maybe an uncountable number. I'm probably one of the more pessimistic people, but that's after all my years watching it. That's how I see it playing out. Unless there's something catastrophic that personally affects individual human people, I'm not sure they will change.”

In the meantime, Julie continues to fight for the exploited. “I want to go to my grave knowing I did everything I could within my means and within the resources I had available to me to reduce suffering because that's all I can do.”

If you want to learn more about Zoocheck and support their work, please visit https://www.zoocheck.com/.

Amazing story! Thank you for sharing!